Elisabeth of Hungary

| Princess Saint Elizabeth of Hungary | |

|---|---|

The Charity of St. Elizabeth of Hungary by Edmund Blair Leighton (1895) |

|

| Widow | |

| Born | July 7, 1207 Pressburg, Kingdom of Hungary (modern-day Bratislava, Slovakia) |

| Died | November 17, 1231 (aged 24) Marburg, Landgraviate of Thuringia, Holy Roman Empire (modern-day Hesse, Germany) |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church Anglican Church Lutheran Church |

| Canonized | May 28, 1235, Perugia, Italy by Pope Gregory IX |

| Major shrine | Elisabeth Church (Marburg) |

| Feast | November 17 November 19 (General Roman Calendar 1670-1969)[1] |

| Attributes | Roses, Crown, Food basket |

| Patronage | hospitals, nurses, bakers, brides, countesses, dying children, exiles, homeless people, lacemakers, tertiaries and widows |

Saint Elizabeth of Hungary (German: Heilige Elisabeth von Thüringen or Heilige Elisabeth von Ungarn, Hungarian: Árpád-házi Szent Erzsébet, July 7, 1207 – November 17, 1231)[2] was a princess of Hungary and a Catholic saint, celebrated mainly in Germany and Hungary.[3] According to tradition, she was born in the castle of Sárospatak, Hungary, on July 7, 1207.[4][5][6] She was the daughter of King Andrew II of Hungary and Gertrude of Andechs-Merania, and at age four was brought to the court of the rulers of Thuringia in Central Germany, to become a future bride who would reinforce political alliances between the families. Elisabeth was married at the age of fourteen, widowed at twenty, relinquished her wealth to the poor, built hospitals, and became a symbol of Christian charity in Germany and elsewhere after her death at the age of twenty-four.

Contents |

Early life and marriage

A sermon printed in 1497 by the Franciscan Osvaldus de Lasco, a church official in Hungary, is the first to name Sárospatak as the saint's birthplace, perhaps building on local tradition. The veracity of this account is not without reproach: Osvaldus also transforms the miracle of the roses (see below) to Elizabeth's childhood in Sárospatak, and has her leave Hungary at the age of five.[7]

According to more contemporary and very trustworthy sources, Elizabeth left Hungary at the age of four, to become betrothed to Ludwig IV of Thuringia. Some have suggested that Ludwig's brother Hermann was in fact the eldest, and that she was first betrothed to him until his death in 1232, but this is doubtful. An event of this magnitude would almost certainly be mentioned at least once in the many original sources at our disposal, and this is not the case. Rather, the 14th-century "Cronica Reinhardsbrunnensis" specifically names Hermann as the second son. In addition, the only contemporary document (dated May 29, 1214) that might support Hermann's claim to be the eldest by putting his name before Ludwig's relates to a monastery in Hesse. This, it has been suggested, actually supports the claim that Hermann was the younger of the two, as Hesse was traditionally the domain of the second son, and thus it would be normal that his name be mentioned first, as this document deals with his territory.[8]

In 1221, at the age of fourteen, Elizabeth married Ludwig; the same year he was crowned Ludwig IV, and the marriage appears to have been happy. In 1223, Franciscan monks arrived, and the teenage Elizabeth not only learned about the ideals of Francis of Assisi, but started to live them. Ludwig was not upset by his wife's charitable efforts, believing that the distribution of his wealth to the poor would bring eternal reward; he is venerated in Thuringia as a saint (without being canonized by the Church, unlike his wife).

It was also about this time that the priest and later inquisitor Konrad von Marburg--a harsh man--gained considerable power over Elizabeth, when he was appointed as her confessor.

In the spring of 1226, when floods, famine, and plague wrought havoc in Thuringia, Ludwig, a staunch supporter of the Hohenstaufen Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, represented Frederick II at the Reichstag (Imperial Diet) in Cremona. Elizabeth assumed control of affairs and distributed alms in all parts of their territory, even giving away state robes and ornaments to the poor. Below the Wartburg Castle, she built a hospital with twenty-eight beds and visited the inmates daily to attend to them.

Elizabeth's life changed irrevocably on September 11, 1227 when Ludwig, en route to join the Sixth Crusade, died of the plague in Otranto, Italy. His remains were returned to Elisabeth in 1228 and deposited in Reinhardsbrunn; on hearing the news of her husband's death, Elisabeth is reported to have said, "He is dead. He is dead. It is to me as if the whole world died today."[9]

Widowed at the age of twenty

After Ludwig's death, his brother Heinrich Raspe of Thuringia assumed the regency during the minority of Elisabeth's eldest child, Landgrave Hermann II, Landgraf of Thuringia (1222–1241).

After bitter arguments over the disposal of her dowry, a conflict in which Konrad had been appointed as her defensor by Pope Gregory IX, Elisabeth left the court at Wartburg and moved to Marburg in Hesse. Popular tradition has it that she was cast out by Heinrich, but this does not stand up to critical examination.

Following her husband's death, Elisabeth made solemn vows to Konrad similar to those of a nun. These vows included celibacy, as well as complete obedience to Konrad as her confessor and spiritual adviser. Konrad's treatment of Elisabeth was extremely harsh, and he held her to standards of behavior which were almost impossible to meet. Among the punishments he is alleged to have ordered were physical beatings; he also ordered her to send away her three children. Her pledge to celibacy proved a hindrance to her family's political ambitions. In fact, Elisabeth was more or less held hostage at Pottenstein, Bavaria, the castle of her uncle, Bishop Ekbert of Bamberg, in an effort to force her to consider remarrying. Elisabeth, however, held fast to her vow, even threatening to cut off her own nose so that no man would find her attractive enough to marry.[10]

Elisabeth's second child Sophie of Thuringia (1224-1275) married Henry II, Duke of Brabant and was the ancestress of the Landgraves of Hesse, since in the War of the Thuringian Succession she won Hesse for her son Heinrich I, called the Child. Elisabeth's third child, Gertrude of Altenberg (1227-1297), was born several weeks after the death of her father; she became abbess of the convent of Altenberg near Wetzlar.

After unsuccessful attempts to force her to remarry, she became affiliated with the Third Order of St. Francis, a lay Franciscan group, but perhaps without becoming an official Tertiary, and built a hospital at Marburg for the poor and the sick with the money from her dowry.

In 1231, Elisabeth died in Marburg at only twenty-four years of age, either from physical exhaustion due to Konrad's treatment, or from disease.

Legacy

Very soon after the death of Elisabeth, miracles were reported that happened at her grave in the church of the hospital, especially miracles of healing. On the suggestion of Konrad, and by papal command, examinations were held of those who had been healed between August, 1232, and January, 1235. The results of those examinations was supplemented by a brief vita of the saint-to-be, and together with the testimony of Elisabeth's handmaidens (bound in a booklet called the Libellus de dictis quatuor ancillarum s. Elisabeth confectus), proved sufficient reason for the quick canonization of Elisabeth on 27 May 1235 in Perugia--no doubt helped along by her family's power and influence. Very soon after her death, hagiographical texts of her life appeared all over Germany, the most famous being Dietrich of Apolda's Vita S. Elisabeth, which was written between 1289 and 1297.

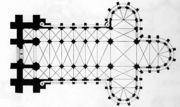

She was canonized by Pope Gregory IX in the year 1235. This papal charter is on display in the "Schatzkammer" of the Deutschordenskirche in Vienna, Austria. Her body was laid in a magnificent golden shrine--still to be seen today--in the Elisabeth Church (Marburg). It is now a Protestant church, but has spaces set aside for Catholic worship. Marburg became a center of the Teutonic Order which adopted St Elisabeth as its second patroness. The Order remained in Marburg until its official dissolution by Napoleon I of France in 1803.

Elisabeth is perhaps best known for the legend which says that whilst she was taking bread to the poor in secret, her husband asked her what was in the pouch; Elisabeth opened it and the bread turned into roses, although this is probably not true, because Ludwig was never upset with Elisabeth for serving the poor. This miracle is commemorated in almost all images of the saints--prayer cards, statues, paintings. One famous statue is in Budapest, in front of the neo-Gothic church dedicated to her at Roses' Square (Rózsák tere) [1].

Another popular story about St. Elisabeth, also found in Dietrich of Apolda's Vita, relates how she laid a leper in the bed she shared with her husband. When Ludwig discovered what she had done, he is said to have snatched off the bedclothes in great indignation, but at that instant "Almighty God opened the eyes of his soul, and instead of a leper he saw the figure of Christ crucified stretched upon the bed."

Elisabeth's shrine became one of the main German centers of pilgrimage of the 14th century and early 15th century. During the course of the 15th century, the popularity of the cult of St. Elisabeth slowly faded, though to some extent this was mitigated by an aristocratic devotion to St Elisabeth, since through her daughter Sophia she was an ancestor of many leading aristocratic German families. But three hundred years after her death, one of Elisabeth's many descendants, the Landgrave Philip I "the Magnanimous" of Hesse, a leader of the Protestant Reformation and one of the most important supporters of Martin Luther, raided the church in Marburg and demanded that the Teutonic Order hand over Elisabeth's bones, in order to disperse her relics and thus put an end to the already declining pilgrimages to Marburg. Philip also took away the crowned agate chalice in which St. Elisabeth's head rested, but returned it after being imprisoned by Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor. The chalice was subsequently plundered by Swedish troops during the Thirty Years' War and is now on display at the National Museum in Stockholm. St Elisabeth's skull and some of her bones can be seen at the Convent of St Elisabeth in Vienna; some relics also survive at the shrine in Marburg.

In Portugal, the legend of the miracle of the roses is taught as having happened to Queen St. Elizabeth of Aragon (1271–1336, Raínha Santa Isabel), wife of King Denis of Portugal. When Portuguese tourists visit Germany or Hungary and are surprised to hear the same legend, it is explained to them that the Portuguese Queen, a granddaughter of King Andrew II of Hungary and his second wife, was named after her great-aunt.

The legends are very similar - the Portuguese Queen, when admonished by her husband that she was too generous with the poor who took advantage of her charity, let her folded apron fall and say "But they are only roses, my Lord!" and the bread became roses. Also, like her ancestor, she was a member of the Franciscan Third Order. This Elizabeth also had the reputation of being a very loving and kind person. Like her namesake, she is remembered today as a great saint who always cared for the sick, young, and those who live in poverty.

Also, founded in 1921 in Oakland, CA St. Elizabeth High School was opened. The year 2007 was proclaimed "Elisabeth Year" in Marburg. All year, events commemorating Elisabeth's life and works were held, culminating in a town-wide festival to celebrate the 800th anniversary of her birth on July 7, 2007. Pilgrims came from all over the world for the occasion, which ended with a special service in the Elisabeth Church that evening.

A new musical based on Elisabeth's life, "Elisabeth -- die Legende einer Heiligen" ["Elisabeth -- Legend of a Saint"], starring Sabrina Weckerlin as Elisabeth, Armin Kahn as Ludwig, and Chris Murray as Konrad, premiered in Eisenach in 2007. It was performed in Eisenach and Marburg for two years, and closed in Eisenach in July, 2009.[11][12]

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Elisabeth of Hungary | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Gallery

From Sint Elisabethskerk, Grave, Netherlands |

From Sint Elisabethskerk, Grave, Netherlands |

From Sint Elisabethskerk, Grave, Netherlands |

From Sint Elisabethskerk, Grave, Netherlands |

German 10 euro coin, 2007 |

The Elizabeth Bower, Wartburg. |

Philip Hermogenes Calderon, St. Elizabeth of Hungary's Great Act of Renunciation (1891) |

|

References

- ↑ Calendarium Romanum (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 1969), p. 108

- ↑ Catholic Encyclopedia "St. Elizabeth of Hungary". Catholic Encyclopedia. http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/05389a.htm Catholic Encyclopedia.

- ↑ "Saint Elizabeth of Hungary". Encyclopædia Britannica. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/184889/Saint-Elizabeth-of-Hungary.

- ↑ Albrecht, Thorsten; Atzbach, Rainer (2007). Elisabeth von Thüringen: Leben und Wirkung in Kunst und Kulturgeschichte. Petersberg: Michael Imhof Verlag. p. 7.

- ↑ Ohler, Norbert (2006). Elisabeth von Thüringen: Fürstin im Dienst der Niedrigsten. Gleichen: Muster-Schmidt Verlag. p. 15.

- ↑ Zippert, Christian; Gerhard Jost (2007). Hingabe und Heiterkeit: Vom Leben und Wirken der heiligen Elisabeth. Kassel: Verlag Evangelischer Medienverband. p. 9., 2007), 9.

- ↑ Ortrud Reber, Elizabeth von Thüringen, Landgräfin und Heilige (Regensburg: Pustet, 2006), 33-34.

- ↑ Ortrud Reber, Elisabeth von Thüringen, Landgräfin und Heilige (Regensburg: Pustet, 2006), 58, 199 n. 14.

- ↑ Rainer Koessling, ed. and trans., Leben und Legende der heiligen Elisabeth nach Dietrich von Apolda (Frankfurt am Main: Insel Verlag, 1997), 52.

- ↑ Rainer Koessling, ed. and trans., Leben und Legende der heiligen Elisabeth nach Dietrich von Apolda (Frankfurt am Main: Insel Verlag, 1997), 59.

- ↑ http://www.spotlightmusical.de/

- ↑ http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elisabeth_%E2%80%93_Die_Legende_einer_Heiligen_%28Musical%29

External links

- The Life and Miracles of Saint Elizabeth of Hungary: The Princess who cared for the weak of our world

- "St. Elizabeth of Hungary", on the online Catholic Encyclopedia, 1913 edition

- "Saint Elizabeth of Hungary", on the Patron Saints Index

- "Saint Elisabeth of Thuringia, 1207-2007", biographical article by Michel Aaij